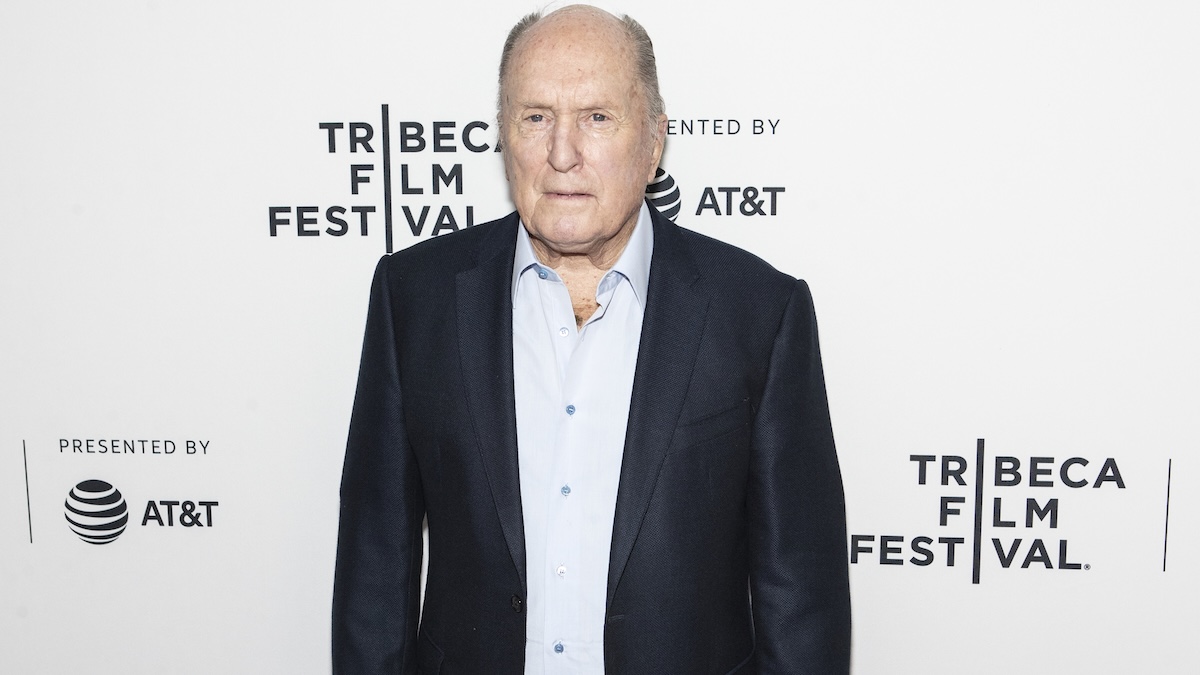

Duvall

Feb. 16th, 2026 06:50 pm

I have, with great pleasure, been reading through Elmore Leonard’s Library of America series, I’m currently reading City Primeval, the 1980 Detroit noir classic that contained a reference to Robert Duvall’s indelible character from Apocalypse Now, which was presumably written not long after it came out. It’s that memorable, and from Tom Hagen to The Apostle there are plenty more where that came from:

Robert Duvall, who drew from a seemingly bottomless reservoir of acting craftsmanship to transform himself into a business-focused Mafia lawyer, a faded country singer, a cynical police detective, a bullying Marine pilot, a surfing-obsessed Vietnam commander, a mysterious Southern recluse and scores of other film, stage and television characters, died on Sunday. He was 95.

His death was announced in a statement by his wife, Luciana Duvall, who said he had died at home but gave no other details. Various news outlets reported he lived in Middleburg, Va.

Mr. Duvall’s singular trait was to immerse himself in roles so deeply that he seemed to almost disappear into them — an ability that was “uncanny, even creepy the first time” it was witnessed, said Bruce Beresford, the Australian who directed him in the 1983 film “Tender Mercies.”

In that film, Mr. Duvall played Mac Sledge, a boozy, washed-up country star who comes to terms with life through marriage to a widow with a young son. The performance earned him an Academy Award for best actor, his sole Oscar in a career that brought him six other nominations in both leading and supporting roles.

My favorite semi-obscure Duvall performance is Jerome Facher, the quietly brilliant corporate lawyer in the fine film version of A Civil Action. But he was almost always great — even in junk like Lucky You he leaves an impression. R.I.P.

The post Duvall appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.

Putin’s perennially unlucky opposition

Feb. 16th, 2026 02:26 pm

How did all these Bolivian toxins end up in Russian politicians?

Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was killed using a poison developed from a dart frog toxin, the UK and European allies have said.

Two years on from the death of Navalny at a Siberian penal colony, Britain and its allies have blamed the Kremlin following analysis of material samples found on his body.

Speaking from the Munich Security Conference, Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper said “only the Russian government had the means, motive and opportunity” to use the poison while Navalny was imprisoned in Russia.

According to Tass news agency Moscow has dismissed the finding as “an information campaign”, but Cooper said there is no explanation for the toxin, called epibatidine, being found.

I believe this is what is called a “non-denial denial.”

While Cooper announced the findings, a joint statement was issued by the UK, Sweden, France, Germany and the Netherlands.

Cooper met with Navalny’s widow Yulia Navalnaya at the conference this weekend.

“Russia saw Navalny as a threat,” Cooper said at the event.

“By using this form of poison the Russian state demonstrated the despicable tools it has at its disposal and the overwhelming fear it has of political opposition,” she added.

In the statement the allies said: “Only the Russian state had the means, motive and opportunity to deploy this lethal toxin to target Navalny during his imprisonment in a Russian penal colony in Siberia, and we hold it responsible for his death.

“Epibatidine can be found naturally in dart frogs in the wild in South America. Dart frogs in captivity do not produce this toxin and it is not found naturally in Russia.

“There is no innocent explanation for its presence in Navalny’s body.”

Next I hope we can get an investigation into why so many Moscow skyscrapers don’t have windows on their upper floors.

The post Putin’s perennially unlucky opposition appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.

My mind is going. I can feel it.

Feb. 16th, 2026 01:54 pm

Except he can’t, because the malignant narcissism leads to, among other things, skipping the whole consciousness of feeling oneself slipping stage:

Now what could possibly have triggered something as apparently random as this? Oh, right:

The discovery that the players of today are far inferior to those of one’s youth, or in Trump’s case, middle age, is not a recent one:

Baseball today is not what it should be. The players do not try to learn all the finer points of the game as in the days of old, but simply try to get by. They content themselves if they get a couple of hits every day or play an errorless game.

When I was playing ball, there was not a move made on the field that did not cause every one of the opposing team to mention something about it. All were trying to figure out why it had been done and to see what the result would be. That same move could never be pulled again without every one on our bench knowing just what was going to happen.

I feel sure that the same conditions do not prevail today. The boys go out to the plate, take a slam at the ball, pray that they’ll get a hit, and let it go at that. They are not fighting as in the days of old. Who ever heard of a gang of ballplayers after losing going into the clubhouse singing at the top of their voices? That’s what happens every day after the games of the present time.

In my days, the players went into the clubhouse after a losing game with murder in their hearts. They would have thrown out any guy on his neck if they had even suspected him of intentions of singing. In my days the man who was responsible for having lost the game was told in man’s way by a lot of men what a rotten ballplayer he really was. It makes me weep to think of the men of the old days who played the game and the boys of today.

It’s positively a shame, and they are getting big money for it, too.

Bill Joyce, quoted in the 1916 Spalding Base Ball Guide

Plato probably said something similar about the Olympiads of his decrepitude.

Returning to our regularly scheduled programming, besides the scientifically confirmable fact that you do not know anyone as stupid as Donald Trump, you just don’t, you also don’t know anyone as intensely miserable as Donald Trump, although he pretty much spends every waking moment trying to alter this situation, by making everyone else as unhappy as only a malignant narcissist can be. That Obama is loved and he never will be — the “love” Trump receives from his supporters is really just reflected hatred, and about as authentic as a prostitute’s smile — is something that positively consumes him with endless rage and frustration.

I take a very un-Christian comfort from the latter fact, as I do from imagining an ahistorical Dante placing Trump at the lowest point of the Ninth Circle, where traitors are frozen in ice, and Satan chews at their feet for eternity, which Trump would spend telling Judas Iscariot about how beloved Trump was back in his day, much much more than Obama, no matter what the fake news and the fake polls said.

The post My mind is going. I can feel it. appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.

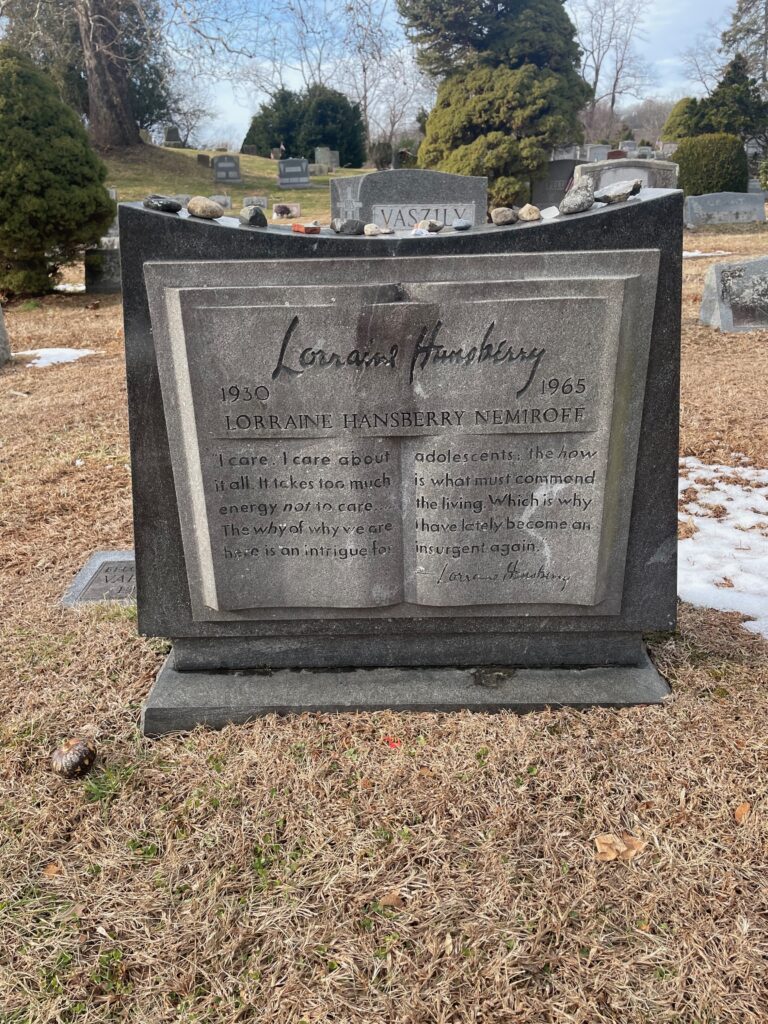

Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 2,083

Feb. 16th, 2026 12:00 pmThis is the grave of Lorraine Hansberry.

Born in 1930 in Chicago, Hansberry grew up in the upper middle class part of the Black community in that city. Her father made a ton of money in real estate. In 1938, they desegregated a white neighborhood, which was a physically risky thing to do. The way this usually worked was that someone would sell a house to a Black family, often because they didn’t care who they sold to and sometimes because they thought integration was good anyway. The locals would be outraged and commit violence and then they would all put their houses up for sale and move to some other cracker land. In this case though, there was a restrictive covenant involved. Hansberry’s father sued and it went all the way to the Supreme Court in 1940. In Hansberry v. Lee, the court decided 6-3 more or less in favor of Hansberry. It didn’t totally strike down restrictive covenants, but it laid the groundwork for Shelley v. Kraemer, which did do that, in 1948.

With that kind of badass background, big things were expected of young Lorraine. She delivered on those expectations. It didn’t hurt that they were friends with everyone–W.E.B. DuBois, Jesse Owens, Duke Ellington, Paul Robeson. Lorraine went to the University of Wisconsin. She became a member of the Communist Party. Her father was a Republican and of course a real estate guy and I wonder how that would have gone, but he had died in 1946 of a heart attack. She was big on the Henry Wallace campaign in 1948 and then did some art training in Guadalajara, embracing the art and social scene in Mexico at a time when it was still pretty welcoming to leftists and artists.

By 1951, Hansberry had moved to New York to get involved in both politics and art. She became enmeshed in the Harlem scene, which perhaps wasn’t quite as groundbreaking in terms of importance as the peak of the Harlem Renaissance 25 years earlier, but was still a critically important site of Black American cultural production. She got to know almost everyone immediately, including all-time legends such as Robeson and DuBois. She worked on Freedom, the important Black paper of the early 50s that brought a lot of discussion of the anti-colonialist struggles into the greater interest readers had in what was going on in the U.S. She started just as a typist but eventually became associate editor.

Shortly after getting to New York, Hansberry married a Jewish activist and songwriter named Robert Nemiroff, but in truth, she was a lesbian who was in the closet for most of her short life, as so many were in the 50s. They separated in 1957 and she started getting in touch with the lesbians in the Daughters of Bilitis, the important early homophile organization that laid so much groundwork for the modern gay rights movement, even if it was on terms that would make contemporary queer activists sometimes feel like they were sellouts (and to be honest, sometimes some of the more radical activists at the time felt that way too). She even started writing–very tentatively–for their magazine, using initials only and just a couple of letters. But she and Nemiroff remained close, even as she slowly moved toward coming out. It didn’t hurt that he wrote a huge hit pop song called “Cindy Oh Cindy,” which was adapted from a Sea Islands folk song and which The Weavers and then The Kingston Trio went big with. So the money from that basically allowed her to write full time without working. They would eventually divorce in 1962, but remained close friends.

Of course, what Hansberry is truly known for today is her 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun, one of the most important plays ever written in this country. She reached back to her Chicago roots for the play about a family whose father died and who will get an insurance payout but then also facing that even money can’t overcome the structural racism faced by Black Americans, particularly in buying a home in a white neighborhood. The play, with its all-Black cast except for one character, had many of the biggest stars of the day in it, most notably Sidney Poitier in the lead, but also Ivan Dixon, Ruby Dee, and Louis Gossett, Jr. After Poitier left the production for other work, Ossie Davis took over the part. This was the first play written by a Black woman to be produced on Broadway. On Opening Night, Hansberry did not want to accept the cheers and accolades the audience provided and so Poitier basically pulled her onto the stage to accept her due. Hansberry also wrote the screenplay for the film version, which of course wasn’t that different.

The success of Raisin in the Sun did forestall much more work happening, though eventually it probably would have. She worked on things, of course. But the only other play she got through to completion and staging in her lifetime was 1962’s The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, which was about a Jewish artist in New York in a bad marriage. I don’t think it was really based on her marriage though. The play was not particularly well-received though. I do wonder how much of that is that reviewers wanted her to focus on the Black experience and not write a play about Jews, a sort of authenticity argument I am sure was part of the story. It got staged in 1964 and by this time, Hansberry was really sick. Gabriell Dell and Rita Moreno were the stars.

Up to the end, Hansberry worked on politics as much as literature. Like many in her generation, she was deeply committed not only to the civil rights cause at home but the anti-colonial cause in Africa. The term “internal colonialism” does such a great job of placing the Black Freedom Struggle in the U.S. in this proper context of global anti-colonialism. James Baldwin set up a meeting with her and Robert Kennedy to push the Kennedy administration on civil rights, which it wasn’t very good at and to the end of her all too short days, she wrote and fought for justice on a global scale.

One of the great tragedies of American letters and really just of America generally is Hansberry developing pancreatic cancer at such a young age. She died in 1965, at the age of 34. One of the biggest “what could have been”s ever. Even outside of her writing, she would have contributed so much to the feminist and gay rights movements as she likely would have been more comfortable on those issues as they became more mainstream.

Lorraine Hansberry is buried in Bethel Cemetery, Croton-on-Hudson, New York.

If you would like this series to visit other American playwrights, you can donate to cover the required expenses here. Neil Simon is in Pound Ridge, New York and August Wilson is in Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania. Previous posts in this series are archived here and here.

The post Erik Visits an American Grave, Part 2,083 appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.

Recreating the Addictive Beat of the Dead or Alive Song ‘You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)’

Feb. 16th, 2026 06:03 pmMusician Captain Pikant used a Hapax sequencer to recreate the incredibly addictive beat of the iconic Dead or Alive song “You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)” from 1984, explaining how this beat is structured to make it eternally recognizable.

“You Spin Me Round” was the career turning point for the British band “Dead or Alive” – and also for Stock Aitken Waterman. …we’re going to recreate its drums on a modern sequencer so you can follow along and use those techniques in your own beats.

subscribe to the Laughing Squid Newsletter

The post Recreating the Addictive Beat of the Dead or Alive Song ‘You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)’ was originally published on Laughing Squid.

How the Industrial Realism of the 1972 Movie ‘Silent Running’ Influenced ‘Star Wars’

Feb. 16th, 2026 04:04 pmFilm essayist Gabe of Golden Flicker did a deep dive into the industrial realism in Silent Running, the 1972 Douglas Trumbull movie that first brought mechanized beings to life, long before such sci-fi classics as Star Wars or WALL-E.

We uncover the hidden history of Silent Running (1972)—the box office failure that became the secret blueprint for George Lucas’s universe.

Gabe also points out that Trumbull created the distinct metallic environment of a spacecraft that would later be used in movies such as Alien. Each effect was made by hand at Trumbull’s workshop, where he, along with a stellar team that included his father, crafted each effect by hand.

From the aircraft carrier set that inspired the industrial look of the Death Star to the amputee actors hidden inside the drones (the direct inspiration for R2-D2), we reveal the physical reality behind the movie magic.

via The Awesomer

subscribe to the Laughing Squid Newsletter

The post How the Industrial Realism of the 1972 Movie ‘Silent Running’ Influenced ‘Star Wars’ was originally published on Laughing Squid.

Kind Woman Gives a Loving Home to an Abandoned English Bulldog Who Showed Up at Her Farm

Feb. 16th, 2026 03:03 pmWhile Andrea Cotter was tending to the goats at her farm in Cornwall, New York, she found an English bulldog with an oversized tongue waiting log near the fence, as if she were expecting someone. Cotter, who lives miles from her neighbors, didn’t understand how this dog ended up on her property.

At first, Andrea was more confused than anything. Her farm is miles and mile away from her closest neighbor. Definitely too far for an English bulldog to simply wander off to.

Andrea immediately gave the dog badly needed food and water. The dog was timid at first, but she soon felt comfortable enough to go inside the house.

She was so loving that Andrea knew she had to be someone’s dog. She’s so sweet She walked right up the stairs and into the house like she knew exactly what living in a home was like. She definitely wasn’t just a stray.

Andrea wanted to know if anyone was looking for this dog, so she took her to the veterinarian to see if she was chipped. Andrea and her husband Christian also filed a police report, posted on social media, and called the Humane Society to see if anyone reported a missing female bulldog. When no one responded, Andrea welcomed “Stella” to the family. Shortly after that, Andrea found out that someone had dumped Stella on her farm in the middle of the night.

Finally, one morning when Andrea was driving along her property line with Stella, she found a tin bowl and a tiny blanket stuffed under a bush. Stella’s owners had dumped her on her farm in the middle of the night and left her there. Andrea was more than happy to officially welcome Stella into her family.

subscribe to the Laughing Squid Newsletter

The post Kind Woman Gives a Loving Home to an Abandoned English Bulldog Who Showed Up at Her Farm was originally published on Laughing Squid.

A really beautiful documentary by Anna Miller Multimedia features Norman Smith, a caring raptor specialist who has worked with Mass Audubon for over 50 years and is known as “The Owl Man of Logan Airport”. Smith spoke about his 43 year mission to relocate wayward snowy owls who land at Logan International Airport in Boston. Smith also shared how he humanely catches the owls, puts a band on their leg for identification, and ensures their health before releasing them back into the wild.

Norman Smith has dedicated his life to protecting and relocating the snowy owls from Boston’s busiest airport runways. Called “the Owl Man of Logan Airport,” Smith has single-handedly relocated more than 900 snowy owls, creating the blueprint for how airports across the US and Canada can manage wildlife conflict.

Smith also expressed his concern for these magnificent creatures and the challenges that they face.

These birds are symbols of the Arctic, and the Arctic is changing. And we don’t know what the future holds for them. My goal and objective in life is just to get people excited about these incredible creatures. The bottom line is we want to get people to care about this world we live in so that we can protect it for future generations.

Previous Snowy Owl Releases

subscribe to the Laughing Squid Newsletter

The post Raptor Specialist Rescues Wayward Snowy Owls at Logan Airport and Releases Them Back Into the Wild was originally published on Laughing Squid.

Wanderlust

Feb. 16th, 2026 07:27 pmFor work-related reasons, I can get a free round trip on any TransPennine Express train.

I'd basically be working on the outbound journey but could come back any time I want, doesn't have to be the same day or anything.

I was excited at having an excuse to go back to York, until I remembered that TPE trains go to Scotland as well... I could go to Edinburgh or Glasgow!

I've got I think four days' vacation I have to use up in March, as well...

It's much longer since I've been to Glasgow, but Edinburgh is closer to where I have friends.

It'd probably mean going on my own though, and that isn't my best thing. But a few days away from Normal Life does sound really nice...

I've got all of next week off work except the Wednesday, which I'll be spending in Chester. It did occur to me that it'd be fun to see how cheap a midweek Premier Inn or whatever would be, and hang out for a few days around the work trip...

I love my house and my people but I like to do different things too.

smbelcas magic linked Stora filten / The big blanket by Linnéa Öhman

Feb. 16th, 2026 01:55 pmsmbelcas magic linked Stora filten / The big blanket by Linnéa Öhman

My first thought was Stora filten / The big blanket which, despite protestations to the contrary, I think I learned about from Kvekk.

Evolution of the sinograph and the word for horse

Feb. 16th, 2026 04:09 pmThis is the regular script form of the Chinese character for horse: 馬.

When I used to give talks in schools, libraries, and retirement homes, anywhere I was invited, I would write 馬 (10 strokes, official in Taiwan) on the blackboard or a large sheet of paper and show it to the audience, then ask them what they thought it meant. Out of the hundreds, if not thousands, of people to whom I showed this character, not one person ever guessed what it signified. When I told those who were assembled that it was a picture of something they were familiar with, nobody got it. When I said it was a picture of a common animal, nobody could recognize what it represented.

All the more, when I showed the audiences the simplified form of the character, 马 (3 strokes, official in the PRC), nobody could get it.

Here is the evolution of this character from the oldest form (about 3,200 years ago) at the top left, going to the top right, then going to the next line and proceeding from left to right, and the same for the third line, and ending with the regular, traditional form and regular, simplified form at the bottom right.

Juha Janhunen assembled a wealth of relevant data in “The horse in East Asia: Reviewing the Linguistic Evidence,” in Victor H. Mair ed.,The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern Central Asia (Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man; Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1998), vol. 1 of 2, pp. 415-430, but didn't draw a firm conclusion concerning possible relatedness between IE words for horse and Central and East Asian words for horse.

Here are Janhunen's latest thoughts (3/3/19, personal communication) on Eurasian words for horse:

I do not see any particular chronological problem in connecting Old Chinese *mra with IE "mare". A possible problem is, however, the geographical distance, as cognates of *mare* do not seem to have been attested in other IE branches except Germanic and Celtic.

However this may be, my point in the 1998 paper was that horse terminology is more diversified in the languages spoken in the region where the horse comes from, and where the wild horse still lives, that is, northern Kazakhstan, East Turkestan, and Mongolia. In view of this it looks like the word *mVrV 'horse' could be originally Mongolic. In any case, it was certainly borrowed from Mongolic to Tungusic (at least twice), and quite probably also to Koreanic (*morV) and Sinitic (*mVrV), from where it spread further to Japonic. From Tungusic it was borrowed to Amuric (Ghilyak). It may also have been borrowed westwards to some branches of IE, if we do not think that the geographical distance is a problem. However, even if the cognates of "mare" can mean 'horse' in general, this does not seem to have been the basic word for 'horse' in PIE. By contrast, in Mongolic *morï/n is the basic word for 'horse', while other items are used for 'stallion' (*adïrga, also in Turkic) and 'mare' (*gexü, not attested in Turkic, but borrowed to Tungusic).

I have always felt that Sinitic mǎ 馬 ("horse") is related to Germanic "mare", though not necessarily directly (from Germanic to Sinitic).

There are some problems, of course, namely:

- "mare" refers to the female of the species.

- Germanic is too late for Sinitic, which had the word mǎ 馬 ("horse") by 1200 BC (though Janhunen doesn't think it's an insuperable problem)

However, the word is also in Celtic (see below), and how far back would that take us?

Even the 5th ed. of the AH Dictionary cites Pokorny 700 "marko", but that may not be a reliable PIE root. Nonetheless, the phonology of the Celtic words alone fits quite well with the Old Sinitic reconstructions for mǎ 馬 ("horse"), namely:

(Baxter–Sagart): /*mˤraʔ/ (Zhengzhang): /*mraːʔ/

Here is what the Online Etymology Dictionary has to say about "mare":

…"female of the horse or any other equine animal," Old English meare, also mere (Mercian), myre (West Saxon), fem. of mearh "horse," from Proto-Germanic *marhijo- "female horse" (source also of Old Saxon meriha, Old Norse merr, Old Frisian merrie, Dutch merrie, Old High German meriha, German Mähre "mare"), said to be of Gaulish origin (compare Irish and Gaelic marc, Welsh march [VHM: ["stallion; steed"], Breton marh "horse").

The fem. form is not recorded in Gothic, and there are no known cognates beyond Germanic and Celtic, so perhaps it is a word from a substrate language. The masc. forms have disappeared in English and German except as disguised in marshal (n.).

So the big questions are:

- how far back do the Celtic words go?

- how are the Germanic and Celtic words related?

- what came before the Celtic and Germanic words? "a word from a substrate language" OR Is Pokorny 700 "marko" for real? (He could not have dreamed it up to satisfy a possible relationship with Sinitic.)

From Axel Schuessler, ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2007), p. 373:

mǎ 馬 ("horse"), Minimal Old Chinese / Sinitic reconstruction *mrâ?

Horse and chariot were introduced into Shang period China around 1200 BC from the west (Shaughnessy HJAS 48, 1988: 189-237). Therefore this word is prob. a loan from a Central Asian language, note Mongolian morin 'horse'. Either the animal has been known to the ST people long before its domesticated version was introduced; or OC and TB languages borrowed the word from the same Central Asian source.

Middle Korean mol also goes back to the Central Asian word, as does Japanese uma, unless it is a loan from CH (Miyake 1997: 195). Tai maaC2 and similar SE Asian forms are CH loans.

So much for horse-related words for now. There are many more posts and comments related to horses, horse chariots, horse riding, and so forth, and more to come.

Next up, we have to figure out the sexagenary cycle of 60 intermeshed 10 Heavenly Stems and 12 Earthly Branches (zodiacal animals) and how 5 duodenary cycles fit into that, horse being the 7th animal in that cycle of 12 zodiacal signs.

Meanwhile, today let's celebrate the Year of the Horse in as many languages as we can think of:

The Horse zodiac sign (seventh in the cycle) represents energy and independence, known as mǎ (马) in Chinese, uma (午) in Japanese, and ngọ in Vietnamese. It is widely recognized in East Asian, Southeast Asian, and related zodiac systems that share the 12-animal cycle, including Thai, Korean, and Mongolian cultures. (AIO)

Hi Yo / Ho Silver, Away!

Selected readings

- "Mare, mǎ ("horse"), etc." (11/17/19)

- "Horse culture comes east" (11/15/20) — with very long bibliography

- "Once more on Sinitic *mraɣ and Celtic and Germanic *marko for 'horse'" (4/28/20)

- "Some Mongolian words for 'horse'" (11/7/19)

- "'Horse Master' in IE and in Sinitic" (11/9/19)

- "Horses, soma, riddles, magi, and animal style art in southern China" (11/11/19)

- "'Horse' and 'language' in Korean" (10/30/19)

- “Of horseriding and Old Sinitic reconstructions” (4/21/19)

- Mair, Victor H. “The Horse in Late Prehistoric China: Wresting Culture and Control from the ‘Barbarians.’” In Marsha Levine, Colin Renfrew, and Katie Boyle, ed. Prehistoric steppe adaptation and the horse, McDonald Institute Monographs. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2003, pp. 163-187 — The domesticated horse, the chariot, and the wheel came to East Asia from the west, and so did horse riding.

At 95 Years Old, Legendary ‘The Godfather’ Star Robert Duvall Has Passed Away.

Feb. 16th, 2026 07:14 pm

Robert Duvall, an actor known for his Oscar-winning and decades-spanning career, has passed away at the age of 95. The news was confirmed on Monday via a statement from his wife, Luciana, on social media.

“Yesterday we said goodbye to my beloved husband, cherished friend, and one of the greatest actors of our time,” Luciana’s statement reads. “Bob passed away peacefully at home, surrounded by love and comfort. To the world, he was an Academy Award-winning actor, a director, a storyteller. To me, he was simply everything. His passion for his craft was matched only by his deep love for characters, a great meal, and holding court. For each of his many roles, Bob gave everything to his characters and to the truth of the human spirit they represented. In doing so, he leaves something lasting and unforgettable to us all. Thank you for the years of support you showed Bob and for giving us this time and privacy to celebrate the memories he leaves behind.”

We have all experienced that rush of adrenaline after scoring a massive tech deal at Walmart. But for this woman, the excitement lasted until she got to the parking lot. One shopper is going viral after documenting the exact moment her “big screen” dreams met the cold, hard reality of trunk space.

TikTok creator Jesica Hatch (@jesicahatch) shared a video of her attempt to fit a gargantuan 85-inch television into her Ford Bronco. Yes, that effort was statistically doomed from the start. But, in Jesica’s own words, she’s just a girl.

Arizona woman asks for a Martini unheard of and still leaves angry: ‘I’d look at her ID again’

Feb. 16th, 2026 07:07 pm

Ever been stuck behind “that” person at the bar who treats a busy bartender like a personal mixology tutor? A recent viral TikTok from creator and bartender Elizabeth Thorne (@elizabeththorne_) has set a new gold standard for beverage-induced confusion. And of course, it has to be a Martini.

In the video, which has amassed over 711,000 views, Elizabeth details an incident a customer asked for a martini. But, she explicitly rejected the very things that make it one. According to her, the woman requested a raspberry martini using Tito’s. When Elizabeth explained to her that drink doesn’t exist and offered a substitute, she agreed.

A woman got hit by a car after visiting the Dallas Parke sample sale. TikToker McKinley (@kin.taylor), who has never made a post on TikTok before, specifically created one to describe the “pure chaos” she witnessed at the sale. She it attracted over 2,000 people.

In her video, which has over 309,000 views, she described how a car hit her and two other women. McKinley was luckily unharmed but not unnerved. The situation made her feel incredibly unsafe

Fellow Figure Skater Defends Ilia Malinin When Internet Uses Teenage Remarks Against Him

Feb. 16th, 2026 06:23 pm

Ilia Malinin had a rough weekend on social media. But, one of his fellow figure skaters stepped up on his behalf during the firestorm.

People uncovered some social media posts from when Malinin was a teenager. A fan asked Ilia if he needed to prove he was straight. The skater responded, “Bro, you know, let’s be honest, I can’t be straight anymore because I need those (artistic) component scores up, you know. I gotta say that I’m not straight, that way my components are gonna go up.” He’s taking a beating for it. On X, Theo Foxx clearly had enough. He stood up for Malinin amidst all this media attention.

Cereal is a breakfast staple among many people. It’s a convenient meal where you choose your favorite flavor, dump it in a bowl, and add your milk. Once it’s time to close the box, you may fold the flaps and slide them under the seal tab. After all, that’s what most of us have been taught, right?

But this woman imparts knowledge on an alternative method she discovered.

First, There Was the 90s Obsession. Now, There Is the FX Series Giving New Fans Love for JFK Jr.

Feb. 16th, 2026 04:00 pm

I grew up in the 90s. My mother, one of my best friends, was a woman who worked in fashion and loved celebrities and their gossip. Meaning she loved John F. Kennedy Jr. and I grew up knowing all about him. So the new series, Love Story, which focuses on his relationship with Carolyn Bessette is right up my alley.

JFK Jr. (Paul Anthony Kelly) was a New York socialite and the son of former President John F. Kennedy. His widow, Jackie Kennedy Onassis (Naomi Watts), and their son had a close relationship and it was one that has always fascinated Americans. Think of the Kennedys as our Royal Family. What Love Story does though is show how the playboy, who dated women like Daryl Hannah (played by Dree Hemingway) and Sarah Jessica Parker, fell madly in love with the fashion icon.